The Genogram in Systemic Personality Analysis

Systemic personality analysis (SPA) describes the structure and content of a single personality. It serves the purpose of investigating and describing a person’s personality potential in such a way that the individuality of his/her actions is recognisable both for the person concerned and the analyst carrying out the task he has been assigned. SPA can

be a part of a pedagogical process, psychological counselling, therapeutic intervention or any form of research into personal resources concerning a particular question or problem. SPA is the product of co-operation between two separate individuals in the roles of expert and client.

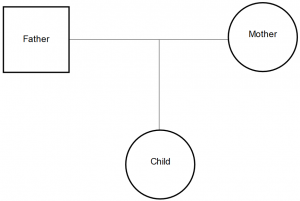

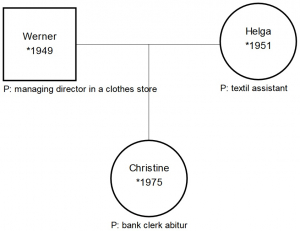

Picture 1

Both of those involved put their joint input of their own personal way of organising themselves in the environment and society into the SPA process. In addition, the expert contributes his knowledge and skills with regard to investigating the content matters and structures of other persons, whereas the client provides information about himself. The joint product thus evolves from the provision of personal information by the client and the individual personal selection and processing of this information by the expert. SPA thus contains equal personal components of both persons involved. The quality of the product, SPA, is largely dependent upon two factors: the information provided by the client and the ability of the expert to process this information into a system. In practice, these factors are not independent of each other. It is the task of the expert to create conditions under which the client is able to provide a maximum amount of information. To achieve this, the expert requires: 1st, self-confidence (in the sense of the conscious awareness of his/her own resources, as I presented this in my definition of the term “selconfidence” in my essay entitled “Dialektik der Persönlichkeit” (Johnson, 1995)), 2nd, technical skills, 3rd, historical and sociological knowledge, and 4th, experience. These four components make equal contributions. The further development in the quality of the product requires an increase in all these components.

The Genogram

The genogram comprises the acquisition, selection, analysis and recording of information on a family system. The system structures and selected content matters are depicted diagrammatically. As a general rule, a record is made during the conversation with the client. This takes place openly, i.e., is visible and comprehensible for the client.

Processing the information

I have already presented the theory upon which the acquisition and processing of data in SPA is based in the above-mentioned essay (Johnson, loc. Cit.). What information is acquired and processed depends greatly on the expert’s powers of perception and knowledge. A piece of information understood within a systemic personality analysis is only then of any value when it can be included by the expert in the description of the client’s “program”. Each piece of information perceived thus requires the posing and answering of the question of how it can be included in the historical context of the development of the personality concerned. In contrast to the everyday

processing of information in contact with human beings as well as to established therapeutic or pedagogical ways of thinking, this requires considerable restructuring on the part of the expert. Whereas conventionally one interprets a particular pattern of behaviour or expression of an emotion as a reaction to some external influence, when one describes the external stimulus and the reaction precisely, the additional question now needing to be answered will be where this behaviour originated in the personality “program”. The description of a particular form of behaviour in a particular situation will always be investigated further by a consideration of where the person has “inherited” (in the sense of the adoption of a “program”) behaving in such a way in such a situation from, or what parts of his/her behaviour are in this case “inherited”. Those inexperienced in using SPA often make the mistake of first of all collecting information to later process them into a system. This approach leads to an abundance of

phenomena being described, for which decisive elements of the information with respect to their relationship to the system are missing. They thus remain unrelated, leading to the expert getting lost in a chaos of information. As a reaction to this, after half an hour at the latest the expert and the client decide to terminate the system analysis.

Synthetic and antagonistic processing of inconsistencies

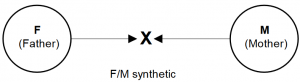

The structure of the origin systems can lead to synthetic and antagonistic inconsistencies within the personality program. Synthetic inconsistencies result from the variability of the paternal and maternal system.

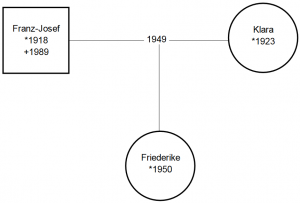

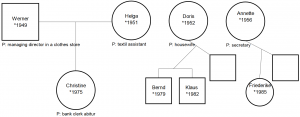

Picture 2

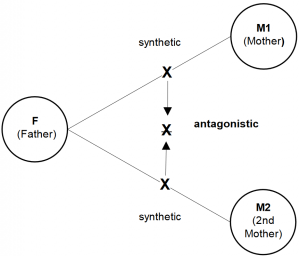

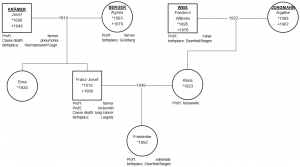

Antagonistic inconsistencies originate from a duplication, e.g.:

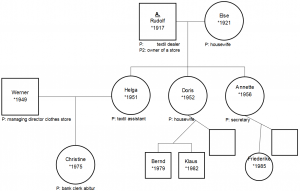

Picture 3

in systemic personality analysis the tracking down and separation of antagonistic inconsistencies is of central importance; their diagrammatic representation is one of the most important tasks of the genogram. Since duplications are often hidden, or at least remain unperceived, as far as the information on the content is concerned, this gives us evidence of such a structure. Antagonisms can be very diverse, and it requires some experience and practice on the part the expert to develop a processing system that effectively uses the information

provided by the client. It is to be recommended that the difference between synthesis and antagonism is elucidated to the client during the 2nd or 3rd session and to present this diagrammatically (as above.). There are a series of typical signs indicating antagonisms in behaviour and the development of a person. At this point, I would like to list some examples in the form of key phrases:

- frequent change of job, partnership, address

• breaking off of relationships with relatives

• disputes concerning inheritances

• all mental disorders, even when they manifest in siblings (neuroses, psychoses, addiction)

• permanent conflict between siblings

• large differences in profession between siblings (e.g. university degree – blue-collar worker)

• suicidal tendencies.

Antagonistic program-controlled behaviour can be divided into three categories

- a) Discontinuation of identity,

- b) Switching from one identity to another,

- c) Deletion of identity.

Typical behaviour for “discontinuation” comprises initially the working towards a target, shortly before or shortly after reaching the target, however, events or behavioural patterns occur which negate the state achieved (typically: terminating professional training shortly before the examination, breaking off of a partner relationship shortly

before or after getting married). Social identity can be recognised, but is not recorded. In the case of “switching”, there is often a fluctuation between at least two identifiable identities. A target or state can only be reached when by doing so another target or state stands in contrast. For example, a stable partner relationship can only then exist when a second relationship exists at the same time, or, to carry out a profession regarded as having a high social status, a person must simultaneously find fulfilment in their belonging to persons of low social status. “Deletion” negates identity. The person uses his/her energy to prevent certain attitudes, patterns of behaviour, social classifications from becoming discernible. In certain forms of depression and suicidal conditions, deletion is related to the entire existence

Forming hypotheses

The investigated content matters and structural considerations are combined in a system hypothesis. The system hypothesis describes the behaviour as the connection between the program with the demands of the environment. In doing this, consideration is given to the dialectics of the original systems (paternal and maternal family) and it assigns the contents to synthetic or antagonistic structures. The hypothesis is formulated in such a way that by gaining additional information concerning the client’s behaviour and his original families it can be tested. Using this approach, during the course of the SPA, initially simple hypotheses become more complex and develop into a differentiated description of the personality. When forming hypotheses particular attention must be made to ensure that content and structure remain independent factors from one another. It is not sufficient, for example, to elucidate a duplication in the structure of the system, without relating the content matters

of the behaviour to the structure. On the other hand, it is insufficient to describe an antagonism in the content matters without being able to relate it to a structure, i.e., with the persons of a duplication. The content matters of a form of behaviour can often be plausibly related to a part of the original family, e.g., with the system of the mother. If in one’s hypothesis, one does not relativize this connection by reference to the system of the father, one neglects the decisive components for the dynamics of identity development.

Preliminaries

With whom can one develop a genogram?

The genogram is the product (input result) of two independent systems (persons). It can only be developed as such when the expert and the client represent two independent adult personalities in juxtaposition. It is not possible to compile a genogram with a child of a mentally challenged person; unless the members of the family to whom s/he relates are involved in the process.

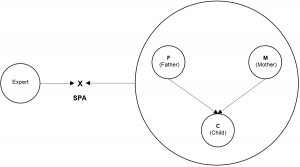

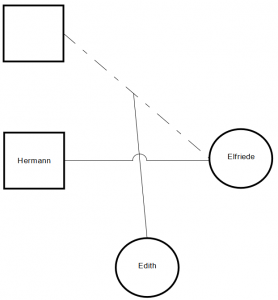

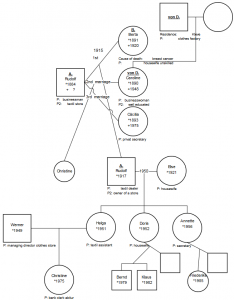

Picture 4

If personal care lies within the responsibility of a person outside the family, this must be taken into account.

The first session: first contact – first discussion

To compile a personality analysis all information can be of relevance, not only what the client expresses verbally. The expert will acquire and process the information gained in accordance with the information processing strategy described below

- what does the person look like,

• how does s/he speak,

• how does s/he look at me,

• how is s/he dressed,

• what car did s/he come in,

• etc., etc.

One begins analysing before the first words have been spoken. When I have written reports before my first personal contact I will already have formed a hypothesis which I can test for the first time at this session.

The client as employer

The first discussion serves to define the task assigned by the client and the expert’s offer and to come to a mutual agreement as to the target to be achieved. I cannot “perform” a personality analysis on a person. The content and goal of the collaboration must be transparent and comprehensible for and desired by both parties. Many experts,

especially therapists and counsellors, have difficulty in appreciating the task the client assigns without an immediate comparison to their range of offers of how to handle it. This easily leads to the expert prescribing the target, so that no mutually agreed target is developed. Under these circumstances, in future collaboration a joint product of two independent systems (persons – subjects) cannot evolve. On the contrary, the client becomes the object of a question or problem of the expert. It is thus prudent to register and record the client’s question or problem with as little interpretation as possible. One general exception to this are clients who have therapy experience. They formulate what they want so precisely for the therapist that it already contains a target agreement. In such cases it is worth asking what matter the client took to a therapist for the first time.

Problem anamnesis

After the client’s problem has been determined, this is followed by compiling a problem and/or system-related anamnesis. This serves the expert in establishing a connection between the identity development of the personality and the problem involved. The problems frequently expressed as a defect or negation are related to the client’s personal program. The first hypotheses are made using synthetic and antagonistic structures. When the task the client assigns involves a symptom, the following questions can be posed:

- when did the symptom occur for the first time (precisely with month and year)

• what is the client’s current occupation

• how does he live

• with whom does he have a permanent relationship

• did the symptom appear in phases

• description of the phases and accompanying circumstances

• what has changed in the personal environment both half a year before and half a year after the symptom manifested

• what decisions were waiting to be dealt with at the time

• what developments proceeded unproblematically

• how did s/he develop her/his way of life since the appearance of the symptom.

When analysing the acquired information one first of all filters out the content matters of a personal and social identification. A hypothesis is then formed as to whether the person discontinues the identification with the help of the symptom, whether s/he switches to a new identification. The questions the expert uses to analyse the information could be as follows, for example:

- what would the client have been or become without the appearance of the symptom

• what content matter of an identification has been prevented by the symptom

• what content matter or identification ensued as a result of the symptom.

I would like to illustrate the procedure with the following example: A young woman who is currently training to become a bank clerk suffers from examination phobias, especially in the field of mathematics. Despite intensive preparation, she fails in the tests and regularly received a 6 (the lowest possible grade). She has no problems in the other school subjects. She has been trying to combat her weakness in performance in mathematics by taking lessons with a private tutor. The tutor confirmed perfectly average mathematical knowledge and capabilities, nevertheless, success did not ensue. The young woman passed her “Abitur” (General certificate of education at advanced level), despite a grade 5 (insufficient) in mathematics. The problems began when she went to grammar school, they did not occur in the primary school. In this example it becomes apparent that a “discontinuation” of an identification with mathematical capabilities is involved. Nevertheless, the presence of this identification will not be completely deleted. The woman did not choose professional training in which mathematics plays no role – on the contrary. The identification theme is constantly circled around without a decision being made in its favour or not. Or, formulated differently: she is good at figures and she is bad at figures. The anamnesis of the symptom showed that she has been good and bad at figures since her 10th birthday without this greatly influencing her school career. Despite this, the woman is suffering from the problem and must summon up a great deal of energy to deal with it. The task set and expressed by the client and the content of this task remain the reference and fixed point for the duration of the entire system analysis process. At all times with reference to the set task the expert must be able to answer the question “why do you want to know that?, and/or “why are we talking about this topic at this very moment?”. Even when the questions are not posed explicitly by the client, the expert should establish the close connection to the point of reference during the discussion.

The expert’s offer

After completing the anamnesis of the problem the counsellor makes a concrete offer. In the case described above, the offer could have been formulated something like the following, for example: “I cannot take this problem away from you, and I do not believe that an expert exists who can invent a solution. I can, however, offer to investigate together with you to find out if you have other inherent capabilities and possibilities to handle the problem differently. Also perhaps how you can cope when the problem cannot be resolved. To do this I must first of all get to know you better, know more about you. I need to know what sort of a personality you are and what strengths you have. The offer to counsel is aimed at the resources of the client. The counsellor does not want to “remove something” in the behaviour and experience of the client or add something foreign to this, he wants to investigate the client’s resources together with him/her and apply the knowledge and insights gained to the handling of the problem. When counselling begins neither the counsellor not the client know the solution or the path to the solution, so that a solution to the problem cannot be offered, only assistance in looking for an approach to solving the problem. For a series of symptoms, e.g., psychoses and addictions, the symptoms themselves comprise the acting out of a duplication in the program. In this case, in the search for a solution to the problem, the client already sees an attack on the approach to solving the problem developed by himself. The point here is to find an approach with which the client him/herself and his/her environment can handle the insolvability of the problem (“the “incurability” of the “disorder”).

Agreement on goals

The basis for the continued co-operation between the client and the expert is a mutual agreement on goals. In the ideal case, this agreement can only be directed toward one final goal. As a general rule, formulated within this final goal will be a long-term interim goal and possibly further shorter interim goals. In every case the agreement on goals must combine the client’s problem and the expert’s offer and be accepted by both parties.

Biographical anamnesis

A large number of patterns of behaviour were already described in the first counselling session and based on the anamnesis of the symptom(s). However, during the later course of the analysis, it is helpful to have a wider basis for the incorporation of the program information into the behaviour of the client. This can be achieved with the aid of a detailed biographical anamnesis. For the biographical anamnesis within an SPA the patterns of behaviour of especial interest are those shown in connection with achieving a new stage of independent identity within the social sphere. This could be a part of a person’s biography (without any claim to completeness)

- learning to speak and to walk

• starting kindergarten

• starting primary school

• transferring to another school

• 1st friendship with a member of the opposite sex

• 1st steady relationship

• school graduation

• choice of and starting vocational or professional training

• test for a driving licence

• finishing vocational or professional training

• 1st car

•1st flat

•1st flat shared with partner

•promotion

•marriage

•1st, 2nd child

• building a house, moving into one’s own house

• death of one or the other parent

• loss of one’s partner, separation

• moving out of the children and their becoming independent

An abundance of hypotheses arise from the data acquired in this way, which can form the basis for an investigation into the problems they contain.

Drawing the genogram

The genogram flow chart is a tool for the expert and the client to jointly depict and discuss the “program”. Since the program only manifests itself in behaviour (performing actions, experiencing emotions, thinking), this behaviour is always the point of reference. Even when the biographical anamnesis is being recorded, one can begin drawing the

genogram. The way this is done should be clear and readily understandable for both parties – client and expert. Traditionally, male persons are represented by squares and female persons by circles. Married couples are joined by continuous, couples by broken lines.

_____________ married couple

———————- couple

Children are attached to the connecting line between the parents

Picture 5

Each symbol is labelled with the Christian name, year of birth and death, the connecting line between a married couple with date of marriage and date of divorce, if applicable.

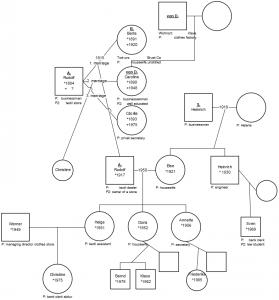

Picture 6

The surnames are written down next to the oldest generation included in the diagram. The symbols can be annotated with additional information. We normally note down the occupations, or professions, place or region of birth, cause of death (especially in the case of death at an early age), general keywords on the special features of the persons and keywords relating to the problem. For purposes of clarity, no more than 5 keywords should be assigned to each symbol. Additional information must be recorded separately.

Picture 7

Duplications are depicted according to the same scheme

Picture 8

In this case Edith is Elfriede’s child with a (still) unknown (biological) father, grown up with (step-)father Herrmann.

Strategic search for information

At first glance the construction of a genogram is similar to the construction of a genogram as in traditional genealogy. However, genealogy ends there where the systemic analysis begins. In genealogy, the actual purpose is the acquisition of verifiable data; they are lined up unconnected. In systemic analysis, data and information only have any value when they can be arranged into system hypotheses and, finally, into a theory of the system. We are thus interested in all information describing the way of life of the individual persons within the family system involved. To analyse a personality systemically, we study its original family, or, preferably – its original families, i.e., its paternal family and its maternal family. The current direct family relationship is of subordinate significance; we consider the partner to be an independent system, the children with the question of what the person has passed on to them. (We shall discuss the choice of a partner as an indication of specific structures within the original system later). Before beginning with the questioning and analysis it is necessary to explain the purpose of the genogram to the client. The words used could be something like: “I need to know from you what your inherent possibilities are in dealing with your environment. I can imagine this best when I know where, what family you come from. I think that much of that used in the organisation of one’s own life or in contact with other people is gained initially from the parents (sometimes I also say: inherited from father and mother). Thus, I would like to know how your family, your parents and grandparents live and have lived in the past.” As a general rule, a discussion ensues from this statement. At this point, however, it is not useful to elucidate the theory. I would like to illustrate the procedure based on an example from my counselling practice: A mother makes an appointment with me for her daughter because she once again failed in school performance tests in mathematics. The mother asks me to help her daughter to pass the examinations and hence not endanger her professional career. The daughter receives an appointment at which she describes her problem in detail. She is 21 years old, has passed her “Abitur” and is currently undergoing training to become a bank clerk. During her entire school career, she had a grade 5 (insufficient) in mathematics. During her private tuition sessions, she was able to solve all the problems correctly, only to regularly fail in the mathematics tests at school. She cannot explain this failure as she has the impression of herself before the test that she fully understands the subject matter. Now the successful completion of her training is endangered as she has a grade 6 (lowest grade possible) in the decisive subject. We discuss the current situation and its history in detail. Based on this, I then make her an offer of investigating jointly what inherent potential with respect to mathematics she has and whether one could possibly exploit this better. I elucidate my concept of how abilities and personal characteristics develop within a person and suggest investigating her original family and to draw in the results on the flipchart available. Drawing the genogram begins with the person him/herself and with his/her siblings. In the example given above we would ask about the school career and naturally the performance of the siblings in mathematics. It would also be of interest what professions the siblings have learnt and carry out. In light of the fact that one sister has trained to become a businesswoman and is now a housewife and mother, we would go on to find out if the siblings are married, or if they have partners and children. Based on the analysis of the siblings’ school performance, we could test our hypothesis on the client’s mathematics program. Unfortunately, in the case under discussion these interesting approaches are inaccessible to us as the client does not have any siblings. We go on to the next item, to the parent generation. First of all – as in the case of all further persons – Christian names, year of birth and, where relevant, year of death are recorded. In addition, the current place of residence is noted down. A detailed and differentiated picture of the parent’s way of life is compiled. When doing this it must be observed that father and mother are different persons. A description is given of how the peculiarities and normality of the persons in the way they lead their lives becomes visible.

Let us demonstrate this approach using a small detail from our example case above:

Picture 9

As we can see, the father is a managing director in a clothes store. I assume that the way he leads his life is an expression of the social status resulting from his job. What make of car will he drive? He will not drive a Golf, Audi,

Opel or Ford – these makes are driven by his employees. He will not drive a foreign car – well-known branded goods are sold in his store. He will thus drive a German status symbol car – true, he drives a Mercedes (with a dark colour, matching the suits he sells). The answer was not difficult to predict, the amount of information content involved here to describe the individuality of the father is small as in the choice of cars he behaves in accordance with a widespread cliché. For our further analysis we can keep in mind that the father places value on fulfilling this status cliché. I discuss this viewpoint with the client, and she confirms that in many areas of life her father stresses the importance on status-orientated behaviour. This can be seen by the clothes he wears, the house built, he plays tennis, etc. I ask if there are also any areas of life in which he is different, the daughter, however, fails to be able to think of anything at this time. I decide to examine at some later point the hypothesis of whether there is a deletion in the original system of the father which does not permit him to have or show individuality. We turn our attention to the mother: she drives a white Golf, says she is indifferent to what car she drives, under no circumstances wants to drive the Mercedes and could imagine owning a convertible. It looks as though, in contrast to her husband, she attaches no importance to demonstrating her social status. Although she appears to fluctuate between whether she should be “conventional” (Golf driver) or “extravagant” (convertible driver). The daughter confirms this interpretation with other examples out of everyday life. The information on the mother gives grounds for the hypothesis that the behaviour depicts a switching structure. In contrast to the father, however, content matters of a possible antagonism are already visible. In my working hypothesis, I speculate about a duplication between systems, of which one is inconspicuous and average and the other is “extraordinary” and possibly of a higher social status. The information on both parents must now be related to the daughter. When doing this too we compare the behaviour of the daughter with the parents, we look for the behaviour of each parent in the daughter; and we analyse the program hypotheses for the parents in the daughter’s program. The daughter drives an Austin Mini, a truly exotic car. Her father chose and bought the car, her mother likes it a lot. The daughter likes it too, but would soon like to buy a Polo. This information requires analytical work on the part of the counsellor. The car is a “cult car”, of which young people in the 60s and 70s dreamed, generally without being able to afford it. Unlikely that the daughter would come up with the idea of buying this car. She confirms that she received it as a gift for her “Abitur” without having chosen it herself.

What does she like about the car?

She likes the fact

- that her parents like it

• that it runs well

• that it looks good.

The thought I expressed that her attitude towards the car could reflect the nature of the conformity of the father and the inconsistent way the mother deals with “extravagance” appears plausible to her, but very unaccustomed. At a later point in time I leave it open to elucidate the question of whether the activity of the father in buying the car and in the choice merely incorporates adaptation (to a general cliché and the wishes of the mother) or whether traces of content matters identifying the personality are to be found.

After we have analysed the parent’s way of life in other areas accordingly and processed them into hypotheses, it is necessary for the first time to investigate the hypothesis relating to the problem in more historical detail. In our example we ask the question: “What were the parent’s grades in mathematics? What have they inherited in this

respect from their parents?” For the father mathematics was never a problem, as far as the mother is concerned the client is unsure and thinks that she probably also had problems. At this point a decision has to be made as to whether first the father’s – or the mother’s system should be investigated further. It is recommended that the side chosen should be the one in which one suspects the duplication with respect to the problem. In this instance both cases should be separated and studied consecutively. In the case under discussion the choice fell onthe mother’s system. We first of all inquire about the mother’s siblings. Using the same procedure used to investigate the client’s siblings (whenever there are any), the parent’s siblings are studied and the information gained incorporated into the hypotheses and theories relating to the family concerned in each case. In this context, the children of the parent’s siblings, i.e., the client’s cousins, can be taken into account. If already based on the problem or symptoms of the client, a duplicate system as the source is probable – as in the case of a psychosis, for example –, although no hypothesis concerning the origin of the relevant duplication can be developed, one should gain a short overall picture of cousins from both sides. As a general rule, it is possible to determine distinct consecutive symptoms of a duplication, so that this side is investigated first.

In our example case, we could already make a decision in advance.

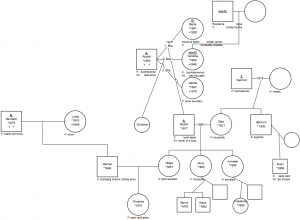

Picture 10

We examine the two hypotheses, according to which “good at figures – bad at figures” and “inconspicuous – exotic” could stand in an antagonistic relationship. The client is asked to question her mother, from whom she then receives answers given willingly. Her aunt Doris was especially good at figures in school, today she lives “inconspicuously” as a housewife and takes care of her husband and children. Like her cousin, her son Bernd constantly had bad grades in mathematics. He graduated from the Realschule (Secondary Modern School) and did an apprenticeship in the metal industry trade. Son Klaus is considered to be the best at mathematics in his class. Aunt Annette passes herself off as being a “refined lady”: her performance in mathematics at school was neither particularly good nor bad. Our antagonism hypothesis grows. We find a typical division of characteristics as they occur in the next generations after a duplication. One sister is good at figures (the one pole), one sister is bad at figures (the other pole), the thrid sister has some of both. We also find our hypothesis substantiated with respect to the characteristic “conspicuously exotic – inconspicuous”. The client goes on to describe that her mother and her aunt Doris had a discordant yet close relationship to each other. This I also consider to indicate that we are on the right path in our investigations. During the further course of the discussion, I first of all explain to my client in general terms my concrete theory of duplications and my concrete hypothesis. I ask her to question her grandparents about any possible stepparents as she herself only knows a little about the grandparent’s original family. Just as in the transition from the client generation to the parent generation, we proceed in the same way in the transition from the parent generation to the grandparent generation (and from the grandparent to the great-grandparent generation). However, it is necessary to follow the effect of every new piece of information back to the client’s problem. The hypotheses developed originally are constantly reviewed and, where necessary, modified

or even completely reformulated. New demands are put on the expert/client team with the transition to the 2nd previous generation with respect to the processing of information. They have to describe the identity of the persons in the context of social values of the living world around them of that time, i.e., as a reference frame they need knowledge of “normality” during that era. This can be illustrated by of a few examples: if someone in the 1930s was a car driver, he was considered to be an “exotic person”. In 1996 someone is considered to be an “exotic person” if he does not have a driving licence and does not drive a car. In 1930 it was extremely unusual and almost “immoral” to take the “Abitur”; in 1996 completing school with the “Abitur” is considered to be “normal”, a difference between boys and girls in this respect is not to be expected. One problem occurring frequently when investigating the grandparent generation is that only little or absolutely no information from immediate personal observation is available: there is some conflicting or embellished handed down information, almost always too fragmentary to be included in the analysis. For the client to be able to conduct the necessary inquiries there are generally two ways, asking relatives or other persons who had corresponding ancestors, and the search for documents. A combination of both approaches is often useful. In the event of disturbed or strained relationships within the family, one should initially try to acquire documents and analyse them. In some counselling or therapeutic cases it can be useful for the counsellor/therapist to actively assist the client in the inquiries. This is especially the case in long-term psychiatric patients and in long-term clients in the addiction sphere. If duplications are suspected, yet are not passed on in the family, marriage and birth certificates often give the first clue concerning a premarital father,

earlier marriages, etc. When comparing data passed down orally with documents, one can from time to time receive the decisive clue concerning a non-inherited duplication. An almost inexhaustible source of information for the description and identification of the individual members of the family are the family photograph collections. As a general rule, the photograph albums are supplied willingly. When looking at these together with the client the trained expert finds many starting-points for forming hypotheses and to integrate into his theory on the client’s program. What information do we then gain in our example case from investigating the grandparents on the mother’s side?

Picture 11

In the next session the client reports a conversation with the grandparents Rudolf and Else. Rudolf was the founder

and is the owner of the haberdashery in which her father is the managing director. The two of them run the business jointly. He still works today at the age of over 80 years old. Due to lack of time, she was unable to do any further investigation on the family. Her grandfather said that he was also poor at figures, it being typical of family A. (grandfather’s surname) that they are bad at figures in school. In response, I permit myself the remark that she must obviously belong to family A., to which she naturally agrees. Being bad at figures is thus a component of family identity of the mother’s family. How can it happen that a family can permanently identify themselves with an undesirable trait? That is the most important question we have to elucidate next in the original system of the grandfather. In addition, our adaptation hypothesis for the father has also received support; he married into his wife’s family business. The grandfather is still (at the age of almost 80) the collaborating entrepreneur. The business bears his name. The grandmother is described as being kind, maternal and with a talent for organisation. She was always good at figures in school. The client believes she has inherited much of her grandmother’s character. In the further course of the session we complete the 2nd previous generation, using the same approach as with the grandparents. From the third generation, the great- grandparent generation, we need at least basic information (names, dates of birth and death, marriage data, places of residence, professions) in order not to depict the second previous generation only descriptively, but to have the means of testing program hypotheses.

Picture 12

In our example case, in this generation we hope to find enlightenment on the unusual characteristic of the family of

being bad at figures. Due the grandfather’s comment on the topic, I first chose his original family for further investigation. In this generation we come across the suspected duplication. The grandfather’s father was a non-dispensing chemist with his own business. Information passed down on his real mother Berta, née B. indicates that she was a simple woman, who had only gone to school for four years. She died early of breast cancer. The stepmother was the daughter of a cloth manufacturer from a town 200 miles away. She was considered refined and educated and was good at figures. She had attended a girls’ high school. With this information we have almost reached the target in the development of a theory on the problem and/or symptom. From the constellation of the duplication in the program in the 3rd previous generation all subsequent generations can be followed. The business-oriented character of the great-grandfather continues without interruption (the client declares here that she definitely wants to take over the business later). The conflict arises in the personal programs between M1 – real mother (simple, uneducated) and M2 – stepmother (refined, educated). The subsequent generations lead a “double life”, in which they do not combine the two forms in a synthesis, but fluctuate between them. In a discussion on the everyday life of the family we become aware of a large number of such “switchovers”. She also realises that her change of car make from Austin Mini to VW Polo is also such a switchover. We can now describe these previously incomprehensible occurrences as being conclusive and consistent in themselves. Both grandmothers survived in the family identity in this way. The plausibility of the theory related to the problem must not induce us to break off our systems analysis at this point. The development of a new quality in self-confidence and the self-realisation of a person requires an equilibrium between the various components of the original system. We start by first going backwards. In the example we add the siblings and then the grandmother’s parents.

Picture 13

The relationship between grandfather and grandmother appears commensurate with their status. Her father was also a self-employed businessman. The client sees similarities in character between herself and her mother’s cousin, who had no problems with mathematics, however. On the other hand, he had problems in his relationships to women. If we look at the late marriage of his father and see that his parents only have one child (just like Christine’s mother), it is not mistaken to suspect an old antagonism in the grandmother’s family as well, having the theme “mother with child –mother without child”. We decide, however, not to continue investigate this further as the client does not pose this question at this moment. We find our theory on the symptom supported by the discovery of two facts. The problem of mathematics is not a topic of discussion in the grandmother’s family and her

descendants. The duplication structure is, however, a probability in her family, where we find experience confirmed that the union between two partners, one of whom one has a “simple”, the other a “duplicate” original structure is very rare. On the other hand, we frequently find a union in which the manifestation of a duplication is shifted by one generation, e.g., in one partner in the second and in another in the third previous generation In the meantime, the client has realised that she knows almost nothing about her father’s family. When asked, the father reacts sceptically and negatively.

Picture 14

Our deletion hypothesis is reinforced by the information gained and the father’s behaviour. In this case it is useful to look for documents. The case description ends here as the client is continuing to investigate. Nevertheless, she has experienced success in getting a grade 3 (satisfactory) in a mathematics test. At the end of our joint discussion she considers it necessary – and possible – to lead a “crazy double life”. Up until this point in time the counselling process has taken three months with four joint sessions. It has proved possible to find an essential part of a personal identity in an apparent symptom. Through the new and expanded knowledge of the persons who are

represented in the personality of the client by the symptom, she has gained greater personal elbow-room: the persons can live on in her, even without the weakness with figures. Nevertheless, there is no reason for the counsellor to lean back in satisfaction. The client will now continue her research under less pressure and less intensively. It will perhaps take a couple years until she reaches the point at which it is necessary in the analysis of

her system to continue with her father’s side.

copyright Helmut Johnson 1994